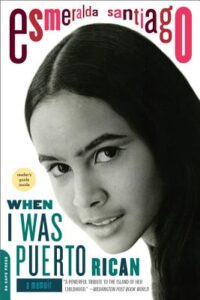

When I Was Puerto Rican

is one of my favorite memoirs. I read it years ago, and immediately bought a copy for my brother as well. I just read it again a few weeks ago, and loved it all over again. The first time I read it, I focused on the story of Negi (Esmeralda’s nickname) and her journey from the slums of Puerto Rico to the slums of Brooklyn, and then to the Performing Arts high school in New York City.

The second time I read this book, I was especially struck by Santiago’s sensory language. Here is the beginning of the first chapter: “We came to Macun when I was four, to a rectangle of rippled metal sheets on stilts hovering in the middle of a circle of red dirt. Our home was a giant version of the lard cans used to haul water from the public fountain. Its windows and doors were also metal, and, as we stepped in, I touched the wall and burned my fingers.” Negi helps her father tear up the house’s floor in order to fix it: “I followed him holding a can into which he dropped the straight nails, still usable. My fingers itched with a rust-colored powder, and when I licked them, a dry, metallic taste curled the tip of my tongue.”

And here is Negi’s first impression of Brooklyn: “Rain had slicked the streets into shiny, reflective tunnels lined with skyscrapers whose tops disappeared into the mist. Lampposts shed uneven silver circles of light whose edges faded to gray. An empty trash can chained to a parking meter banged and rolled from side to side, and its lid, also chained, flipped and flapped in the wind like a kite on a short string.”

The entire book is effortlessly sensory in a down-to-earth way. Negi’s play with her many siblings; her parents’ awful fighting; her family’s months of living in a floating house on a lagoon full of sewage; her hilarious interview for the Performing Arts high school; it’s all here in full-body detail.

Although this book ends with Negi’s acceptance to the Performing Arts high school, there is a sequel: Almost a Woman, about her life as a teenager and young adult. I remember enjoying this book as well.

Santiago published a third volume of memoir, The Turkish Lover, which I have not yet read.