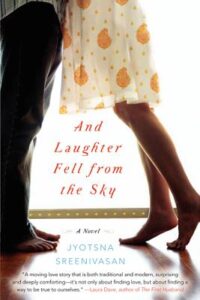

My new novel, And Laughter Fell from the Sky

, is a love story and a story about searching for one’s path in life. It has been described as “a witty, timely exploration of the varying definitions of success, belonging, cultural identity, and the human desire to connect” (according to a review in Booklist). My intention was to write an entertaining novel with interesting characters who had things to learn, and to explore some of the issues faced by second generation Americans. Although this book is not at all autobiographical, still I am very familiar with the pressures and conflicts the characters face as a result of trying to straddle two cultures.

Here are some reviews:

- Lovely review from Colleen at Books in the City

- Thought-provoking review by Anjana Vasan

- If The House of Mirth Were Written Today, it Would Be And Laughter Fell from the Sky, review by Diane LaRue

- Review by Swapna Krishna

Here are some Reading Group questions.

I’m interested to see how readers of immigrant and second generation literature react to this novel. Feel free to leave a comment.