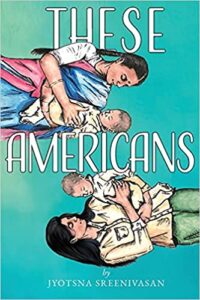

I’m so excited to introduce my new book of short stories and a novella, These Americans. These women-centered stories are based on my life growing up Indian-American in the Midwest.

I’m so excited to introduce my new book of short stories and a novella, These Americans. These women-centered stories are based on my life growing up Indian-American in the Midwest.

The book won a bronze award in the Foreword Reviews INDIES awards in the multicultural category!

Check out this short introductory video about These Americans. This video is part of the Lakewood (Cleveland) public library’s Meet the Author series.

Access reading group discussion questions, and find out how to invite me to a virtual Q & A session with your class or group, by clicking here.

These Americans explores what it means to live between Indian culture and American expectations. An Indian-born immigrant mother gives birth to her daughter in a small Ohio town. A girl recently returned from India strives to become “American” again. A naïve immigrant mother is in denial about her lawyer daughter’s lesbianism. An elderly doctor keeps a shocking secret from her daughter.

This collection won the Rosemary Daniell Fiction Prize from the publisher (Minerva Rising Press). The novella, “Hawk,” is a revised version of the novel “On the Brink of Bloom,” which was a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize in 2014.

You can buy These Americans from Amazon.com, or Bookshop.org (to support independent bookstores).

If you wish, you may read some excerpts (1st page of each story).

The title, These Americans, comes from a phrase that my immigrant parents often said to refer to non-immigrant Americans. Often, the phrase was used as a way to contrast their Indian culture with the mainstream American culture, as in “I have gotten used to these Americans smiling all the time.” (This is a quote from the first story in the collection.) But the phrase “these Americans” can also refer to immigrants and their children because, after all, we are Americans too.

Here are some nice things people have said about the book:

“Readers looking for accessible short stories capturing immigrant experiences and women’s lives will find These Americans a study in contrasting cultures. . . . Thought-provoking, diverse, yet interconnected by Indian heritage, American experience, and women’s lives and concerns, These Americans offers a rich set of insights.”

“Sreenivasan brings her characters to life, and in reading these stories that move from birth to death we learn the breadth of what it means to be an Indian-American, to try to blend your own culture with the culture of the people now surrounding you. These Americans will help you to be more empathetic to others, a goal of reading great fiction. I highly recommend it.”

• Diane LaRue, BookChickDi Blog

- Margot Livesey, award-winning author of Mercury and The Hidden Machinery

“Jyotsna Sreenivasan’s short stories are clearly, and aptly entitled: These Americans. These are stories about everyday Indian American people in the United States. We learn more details of lives that are lived parallel to the mainstream, Hollywood vision of America. The stories are a valuable addition to the more complex panorama of American life that readers are, at last, eager to read.”

- Breena Clarke, author of River, Cross My Heart (Oprah book club selection) and Stand the Storm (named one of the 100 best books of 2008 by the Washington Post)

“A quietly tender–and occasionally hilarious–meditation on life, family, and immigration.”

- Marie Myung-Ok Lee, author of The Evening Hero and Finding My Voice and a founder of the Asian American Writer’s Workshop

Click here for more reviews and interviews about These Americans.