I don’t know if Barack Obama would consider himself a “second generation” American. His Kenyan father was not technically an immigrant, although he studied in the United States for many years, earning a graduate degree at Harvard University. Barack’s mother was a white woman named Ann Dunham. The marriage deteriorated soon after Ann gave birth to their son, and the elder Obama eventually returned to Kenya. He died in 1982, when his son was in college.

I don’t know if Barack Obama would consider himself a “second generation” American. His Kenyan father was not technically an immigrant, although he studied in the United States for many years, earning a graduate degree at Harvard University. Barack’s mother was a white woman named Ann Dunham. The marriage deteriorated soon after Ann gave birth to their son, and the elder Obama eventually returned to Kenya. He died in 1982, when his son was in college.

But although Barack Obama did not grow up with his father, and in fact spent only one month with him when his father came to visit his 10-year-old son in Hawaii, his Kenyan name and his brown skin were a constant reminder that he straddled two worlds, just as many second-generation Americans do.

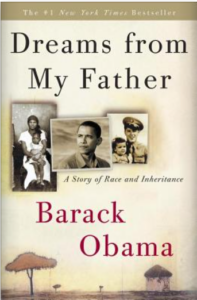

Obama wrote Dreams from My Father when he was just out of law school, before he got into politics. He was invited to write the book after becoming the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review. The front cover shows a photo of him as an adult, positioned between a photo of his dark father as a young child on the lap of his mother, and a photo of his pale mother as a young child with her father.

Obama struggled to make sense of his identity. One example: he cringes when, on the first day of fifth grade, his teacher, in front of the entire class, mentions that she used to live in Kenya and asks what tribe his father is from. Obama’s white grandparents (who raised him while his mother lived in Indonesia with her second husband) do not understand the young Barack’s embarrassment. “ ‘Isn’t it terrific that Miss Hefty used to live in Kenya?’ “ his grandfather asks. “ ‘Makes the first day a little easier, I’ll bet.’ “ Barack doesn’t even try to explain. “I went to my room and closed the door” (p. 60).

As a teen, Obama is drawn to some of his grandfather’s African-American friends. He develops a passion for basketball. After college, he takes a job as a community organizer in an African-American neighborhood in Chicago. Yet he cannot seamlessly fit in with African-Americans either. He does not come from their legacy of slavery and segregation. His heritage is elsewhere, across the ocean. In Chicago, he hesitated to share his background with the poor African-Americans he was helping to organize. “I was afraid . . . that my prior life would be too foreign for South Side sensibilities, that I might somehow disturb people’s expectations of me” (p. 190).

Obama always knew about his family in Kenya, but it wasn’t until he visited Kenya, just before entering law school, that he began to fill the “great emptiness” he found inside himself (p. 302). In Kenya, he dances and feasts with his half-siblings. He learns about family conflicts. He hears, from his grandmother (as translated by his sister), the story of his ancestors and especially his father. And he experiences a catharsis as he weeps at his father’s grave.

“I saw that my life in America—the black life, the white life, the sense of abandonment I’d felt as a boy, the frustration and hope I’d witnessed in Chicago—all of it was connected with this small plot of earth an ocean away, connected by more than the accident of a name or the color of my skin” (p. 430).

I would argue that Barack Obama’s divided cultural heritage prompted him to explore more deeply what it means to be an American, and led him to become the President of the United States. He says as much in his new book, A Promised Land: “Ultimately wasn’t this what I was after—a politics that bridged America’s racial, ethnic, and religious divides, as well as the many strands of my own life? . . . . As I gave the future more thought, one thing became clear. The kind of bridge-building politics I imagined wasn’t suited to a congressional race. . . . To really shake things up, I realized, I needed to speak to and for the widest possible audience” (pp. 41-42).