The first 6 pages of When We Were Sisters do not invite the reader in. These pages are written from the distant point of view of an uncaring universe. We learn that an unnamed man has been murdered in an unnamed city—not the one he was born in, but where his children were born. We learn that upon his death, the man’s brother-in-law, who married a white American woman, “celebrates” by renovating his house. We learn that the murdered man’s wife has also died, leaving the orphaned nieces with “their dead dad’s money up for grabs.” The brother-in-law’s white wife refuses to take in the orphans, so the man promises, “It’ll be like they never existed.” The reader struggles to understand and to care about these people.

From this distant beginning, the novel plunges us into a very personal, first-person story from the point of view of a little girl with two older sisters. We gather that these girls are the orphans, and that their father has been murdered. Because the novel starts from the point of view of the little girl, the situation is confusing to the reader, as it was to little Kausar. An uncle takes them to an apartment he owns, which they must share with many caged birds and other animals. Gradually, we learn that the uncle, whose name is blacked out throughout the novel, is using their father’s money, as well as the government checks that each girl receives, while keeping them isolated and in poverty, sometimes without even money for food. The uncle eventually rents another room of the apartment to a couple newly arrived from Pakistan. This couple begins to take care of the girls, acting as parent figures. However, when the uncle finds out about the bond between this couple and the girls, he evicts the couple. The girls must grow up on their own.

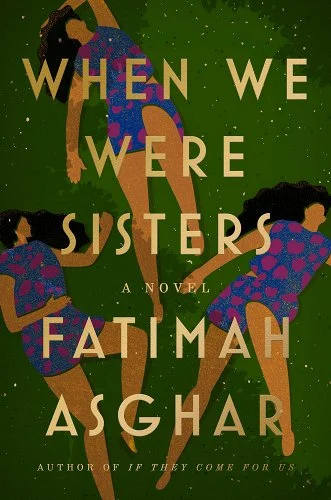

Most parts of the novel are in prose. However, Fatimah Asghar, who is also a poet, has also included several poems, as well as a few experimental sections. One passage, printed sideways, has many words missing, with the missing words printed on the facing page. Although I don’t normally enjoy experimental novels, in this case I was drawn in by Kausar’s intensely emotional story. The piecemeal way the story is told reflects Kausar’s fragmented view of life.

This novel is somewhat different from many of the other second-generation novels I’ve reviewed. Kausar does deal with the usual questions about where she is from. At one point, she is called “Pocahontas” (p. 106). However, her suffering and struggles as an orphan and as a survivor of abuse overshadow her attempts to navigate her Pakistani heritage and her American reality.

I was curious about whether the story was based on the author’s life. In an interview, Asghar said that, like Kausar, she is an orphan with two sisters. She says the book has “auto-fictional elements.” I highly recommend this novel. Stick with it past the difficult first pages, and I think you will be as absorbed as I was in this deeply moving story.