Back in 1991, when I was a young, struggling fiction writer living in Washington, DC, who hadn’t published much of anything, I read a wonderful story in a literary magazine by a woman named Julia Alvarez. In preparation for this blog post I looked at Alvarez’s list of publications to refresh my memory, and I believe the story I read was “Floor Show”, published in Story magazine.

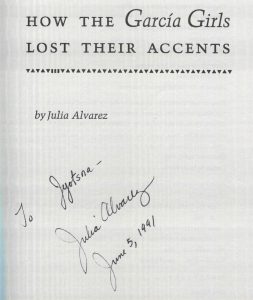

I thought “Floor Show” was warm, interesting, insightful, funny, and authentic—so different from many of the cold, clinical, self-consciously serious stories I often read in literary magazines. I was therefore thrilled to find out that this author was going to give a reading from her new book in a DC bookstore! I was there. I bought her book—How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents—and she signed it for me. I still have that signed copy. I’ve read it several times, and now that she’s a famous author, I feel pride every time I see her name or work—because I knew, back then, how special she was!

I’m going to call How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents a classic. Can a book only 25 years old be a classic? I think so. The farther back you go in literature, the fewer women or writers of color you’ll find, so I’m going to claim the word “classic” for this book. And not just a Latino classic, or a second generation American classic, although it is those things too—but a regular classic with no adjective attached.

How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents is a novel-in-stories. Each story can be read and enjoyed on its own, but each story is also linked to the others through the characters and events. All the stories are about a family with four daughters who fled the Dominican Republic and settled in New York. The stories are arranged in reverse chronological order, from 1989 (when the third daughter, Yolanda, is 29) to 1956 (when Yolanda is a small child). The stories are autobiographical, and Yolanda, who becomes a writer, is the alter-ego of Julia Alvarez. Some of the stories are told in first person singular, one in first person plural (“A Regular Revolution” is told by the four girls together, “we”), and some in third person.

I was going to present a list of my favorite stories, until I realized that almost all the titles would be on it, so my recommendation is: read them all in the order they appear in the book. Since you’ll be reading into the past, it’s fascinating to understand the precursors to the adult challenges the daughters face, and the stories behind the memories alluded to as the girls get older. Every character, major or minor, is clearly and vividly portrayed, and each character is unique. I so enjoyed getting to know the sisters as well as their parents and many relatives.

When I think about the language of these stories, the word “folk art” comes to mind. Although the book jacket tells me that Julia Alvarez has graduate degrees in writing and literature, yet the language seems as open, alive, and unpretentious as a masterpiece from an unschooled artist such as Grandma Moses. I guess what I’m trying to say is that, instead of calling attention to itself and saying “be impressed!” Alvarez’s language takes us by the hand and leads us to fall in love with the characters and their stories.

I might as well end with the beginning of “Floor Show,” that first story that led me to fall in love with this book 25 years ago:

“No elbows, no Cokes, only milk or— ” Mami paused. Which of her four girls could fill in the blank of how they were to behave at the restaurant with the Fannings?

“No elbows on the table,” Sandi guessed.

“She already said that,” Carla accused.

“No fighting, girls!” Mami scolded them all and continued The Epistle. “Only milk or ice water. And I make your orders. Is that clear?”

The four braided and beribboned heads nodded. At moments like this when they all seemed one organism—the four girls—Sandi would get that yearning to wander off into the United States of America by herself and never come back as the second of four girls so close in age.