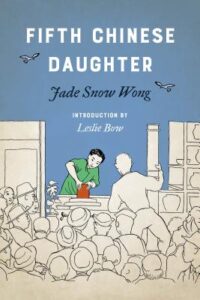

Fifth Chinese Daughter

, first published in 1945, was one of the first memoirs by a Chinese-American. Wong chose to write in third person, rather than first person, because of Chinese habit, as she explains: “The submergence of the individual is literally practiced. In written Chinese, prose or poetry, the word ‘I’ almost never appears, but is understood” (p. xiii).

The third person point of view gives the memoir a formal feel, yet Wong’s simple, direct language is very accessible. In some ways, the book reminded me of the “Little House” books by Laura Ingalls Wilder (also written in third person), partly because Wong spends a lot of time describing the food and customs she grew up around, and also because she gets to the heart of the matter in a succinct, simple, authentic way.

I thoroughly enjoyed the hours I spent reading this book. I read it slowly, savoring each anecdote of this honest and in some ways charming coming-of-age story. As a child, Wong frequently puzzled over the differences between her home life in San Francisco’s Chinatown, where her parents owned a home-based garment factory, and the wider American world. Wong tells of her realization that the very strict upbringing of her home, devoid of outward expressions of love, was not the norm in mainstream American society. When little Jade Snow got hurt at school, her teacher comforted her by holding her close and wiping away her tears: “It was a very strange feeling to be held to a grown-up foreign lady’s bosom,” Wong recalls (p. 20).

Wong was an obedient daughter: she did well in both American public school, and evening Chinese school. However, when she realized that, although her parents funded her older brother’s college education, they had no plans to pay for college for her, she began to break away from the Chinese culture she’d grown up with. As she worked her way through college, she claimed individuality and freedom for herself, daring to go out with a boyfriend without her parents’ permission.

After college, Wong decided to make a living as a potter, an unheard-of profession for a Chinese-American girl. Undaunted, she set about finding a place to rent in Chinatown. Although many in Chinatown thought she was crazy, she was pleased that her father expressed his support by giving her a small motor to run her pottery wheel.

She ended up becoming well known for her vases, bowls, and mugs. Her obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle includes a lovely photo of her working at her pottery wheel.